Why Probe the Sun? For One Reason, to Help Predict a Disaster

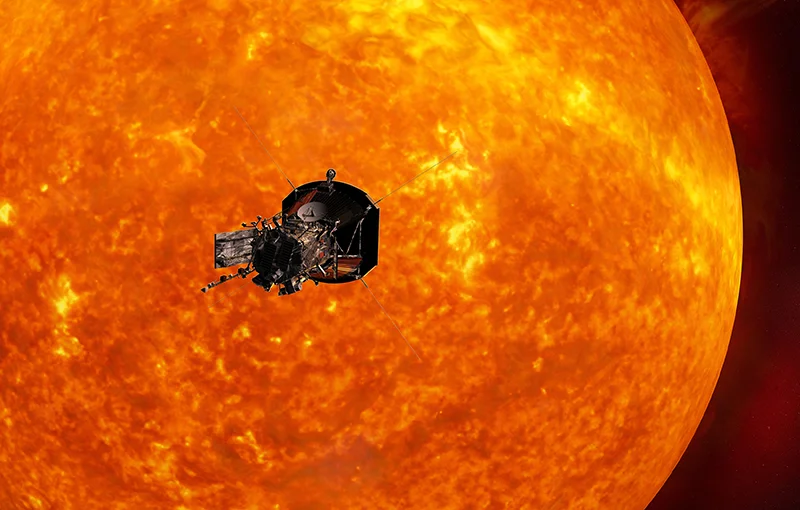

/Artist's concept, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory

Next year, NASA will send up a probe offering further proof that space is anything but empty. The Parker Solar Probe will devote its seven-year mission to studying the Sun’s corona, a band with million-mile-an-hour solar winds carrying temperatures mysteriously greater than the heat on the surface of the Sun itself.

The probe is named after the brilliant University of Chicago astrophysicist William Parker, who calculated the existence of solar wind in 1958—a time when most scientists thought space to be mostly void. “This is ridiculous,” one of the reviewers of his paper said.

Not only has solar wind proven to be very real; scientists have learned since that solar weather weather constantly bathes the earth.

Occasionally, solar storms slam into Earth’s magnetic field like a hurricane battering the coast. One of those solar superstorms, the Carrington Event of 1859, caused nighttime auroras so bright that people in the northeastern states could read their newspapers without aid. Telegraph operators received electric shocks, and their systems failed around the world.

If such an event happened today, it could knock out communications around the world and could cost more than $2 trillion. The U.S. Eastern Seaboard could be without power for a year.

How likely is such an event? A Carrington-sized superstorm just missed Earth in 2012.

That’s why the Parker Solar Probe is well worth the billion-dollar cost. It will help us understand the weather in the Gravity Well much the way we understand weather within our atmosphere. The more we know, the more we can predict—and be prepared for the next superstorm.